On with the motley

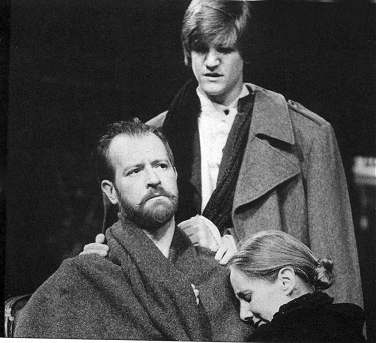

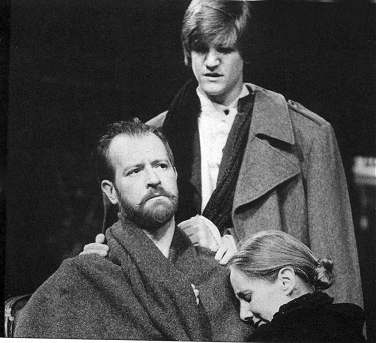

Nicholas Wapshott meets Alan Howard,

returning to the stage

|

This Tuesday Alan Howard again endures first

night nerves - his first rush of stomach-turning adrenalin for over two years.

He will walk, bearded, into a grand, newly-democratised Tsarist railway

carriage on the stage of The Mermaid ina second-hand role left vacant by Daniel

Massey in Stephen Poliakoff's Breaking the Silence.

The last time Howard strode a London stage

seems a different age. He completed a codpiece-breaking stint as both Richard

II and Richard III then turned the house-lights off as he - and the RSC - left

The Aldwych for ever. Since the company has been at The Barbican he has been

elsewhere, though seldom acting.

He took C.P. Taylor's Good to Broadway and

slipped on and off television, most recently in the BBC play The Holy

Experiment as an eighteenth century Jesuit setting up a state within a state in

Spanish South America. But the nearest he got to a British stage was sitting at

a table in the shell of the barely-completed Almeida, reciting War Music about

the Trojan wars with Christopher Logue. |

|

Howard used to be addicted to performance. To have

abandoned the theatre for so long is like Terry Wogan giving up broadcasting or

Keith Richard kissing heroin goodbye. In 1975 he played a string of three

Henrys at Stratford, then took them on tour to London, New York, the regions of

Britain, then Europe. Two years later he added Coriolanus to his Henrys and the

following year tagged on Cleopatra's Antony to take up the slack.

What was all this activity about? Why did he give it

all up? And why is he back to his old tricks, returning to the company which

has become to him like a treadmill to a marathon runner? At first he talks with

his arms, trying to conjure the words, then comes the staccato,

precisely-enunciated delivery, the snatched phrasing which has become his

hallmark.

"A lot os it is circumstantial. You find yourself in

a position where others say, 'Why don't you do this?' and you think, 'I don't

know why I'm saying no to this. Is it because I cannot do it, or wouldn't it be

rather more stimulating to go that much further?' Then you are in a bind partly

of your own choosing. And when others are saying 'Why don't you?' you think

'Let's all go. Why don't we all go a little bit further, a little bit

madder.'

"That amount of pressure has been very fruitful. One

can enter doors, find images one didn't quite believe were there. But I have

also thought that to stop is important as well. It is that thing about doing

things as long as the beauty lasts."

But why do it? Why invite the overcommitment to

projects that lead to constant work? "Well, I think I could be very lazy.

Business does create a busy front, doesn't it? Just lately I haven't been as

busy as I had been and I have quite enjoyed the sort of relaxation that has

surrounded it. But the mania, I haven't missed that once. But I wouldn't mind

if it happened again."

For all his compulsive working and his domination of

the RSC output in the late Seventies, Alan Howard is not a star of the stage in

the conventional sense. Sitting prominently in the middle of a wine bar,

talking animatedly, waving his arms, he attracts no sneaked looks of

recognition. For Howard is that unusual paradox, an introverted actor. To those

who inner doubts are expressed by him on stage, he dominates the plays he is

in. For others of a more flamboyant disposition, he irritates, almost offends,

by his quiet presence.

As he puts it: "I am really not very good at taking

over the floor. I am appalling at any of those occasions, like having to give a

speech or a vote of thanks. Outgoing actors who find that sort of thing easy

represent a great deal of the audience, but then so do I. When I get up onto

the stage, 65% of the people will say: 'Oh God, not him.' But then there are

quite a lot who associate with me and the way I do things."

His style of acting perfectly matches the company

ethos of the subsidised theatre, where directors have become as important as

the actors. Howard finds himself in a similar position to actors like Ian

McKellen, Edward Petherbridge, Daniel Massey and others, whose function is to

forgo the conventional selfishness of actors of a previous generation and

concentrate on representing the notions of the company, the director and, above

all, the authors of the plays.

In Howard's case, of course, this particularly means

revealing Shakespearean roles which have previously been swamped by the

overbearing personality of the actors given the lead roles. Shakespeare has

thus become more authentic, more relevant, more understandable to a modern

audience, as the old story takes precedence over a new career. While some

actors have dismissed the young post-war stage directors as 'puppet-masters,'

Howard and others are evidence of actors bringing a selfless dedication to

their tasks, the puppets of no one.

Nicholas Wapshott

The Observer, 26.5.1985.