How We Met

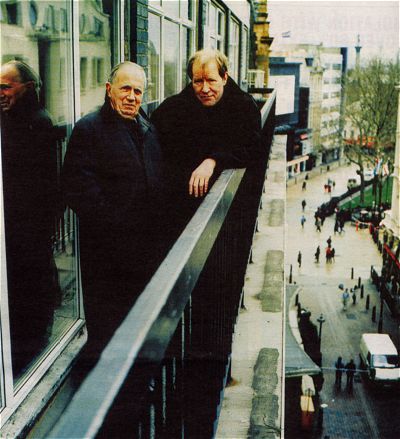

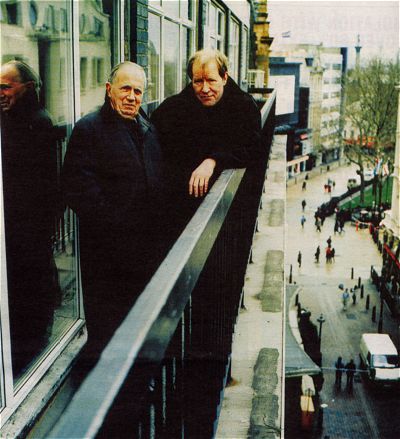

Alan Howard and Christopher Logue

|

The actor Alan Howard (far right) is 59. He

has worked with the RSC and the National Theatre in roles as different as

Coriolanus and Professor Higgins in Pygmalion, and is currently

performing Kings - books one and two of Homer's Iliad. He lives

in north London with his partner, the novelist Sally Beauman. Christopher

Logue, 70, is a poet, playwright, actor and journalist, who published the first

of several volumes of poetry in 1953. His work includes three volumes of an

adaptation of Homer's epic narrative: Kings, The Husbands and

War Music. Between 1961 and 1993 he wrote the True Stories column for

Private Eye. He is married and lives in south London.

|

Alan Howard: I think it was 1981. I was at

Stratford, doing Richard II and Richard III for the RSC and living in a

cottage; we met there. Christopher came with the producer Liane Aukin, who was

recording Christopher's War Music for BBC radio. They wanted me to read

it.

The first thing I noticed about him was his voice,

which is very distinctive and expressive. I knew that this was somebody

passionately concerned with words, which are an obsession of mine. That I found

very attractive. And when I read War Music I was absolutely astounded by

its quality.

I didn't see him again until we started doing the BBC

recording. Christopher would drop in, sit in the box and start making snipy

comments about things, which were sometimes helpful and sometimes weren't. We

rarely get at each other now, but then he would get quite exercised and I'd get

very exercised back. We used to start shouting at each other, a very

constructive form of argy-bargy. He didn't get offended; or he certainly didn't

show it.

After the BBC recording we did a reading. Howard

Davies was running the Donmar Warehouse in about 1982 and was putting on a

mini-festival, and asked whether anyone in the RSC had anything to offer. I

suggested that Christopher read War Music with me. The idea was that

there was a poet and an actor: the poet at the table with his book, and the

child who plays with the words. Then we performed at the Almeida and did gigs

up and down the country.

Between War Music and Kings we've probably performed

together around 50 times. Time that people share on stage in front of the

public is curiously intimate. There's an unspoken closeness. That's what we

share: we've both recognised each other's vulnerabilities as

performers.

Christopher really hates moving; he's happy sitting

behind the table. But he can never understand why I should be nervous. I say,

all actors are nervous. He's very good if I lose the lines, which sometimes

I've been known to do - I knit away in the same rhythm until I get back on line

again. Christopher follows the text in his book. But sometimes he gets so

caught up in it that he loses his way and forgets what page he's on. I notice

sometimes he has to knit as well, even though it's his own text.

We're hopeless at curtain calls. Christopher's even

worse than I am, and I'm pretty bad. We share a similar kind of shyness. It's

over, we don't really want to be there, so we're not very good at the "hey,

it's been a great show, let's give it to them" stuff.

Yet the last thing you'd think is of Christopher

being shy. He's so animated. He has this amazing ebulliance and is quite loud -

which I like because it can free me up a bit. His enthusiasm is very catching,

but he can get terribly down as well. He has a mercurial temperament: he goes

wild very quickly if he decides something is wrong and can be extremely

rebarbative. But he's also got that rare quality of being able to be extremely

rude, coruscatingly rude, without an ounce of malice. I find it funny. And if

he's proven wrong, he'll always write letters of apology to

everybody.

Christopher has a low tolerance threshold for

slightly foolish or inadequate people. Yet I remember once when we were in

Athens, doing War Music, I had a lighter that I'd had for years and had a

sentimental attachment to. I left it behind in this restaurant and it wasn't

until the middle of the next day I realised what I'd done. I thought: "this is

going to be interesting." I said: "I'm going back to find the lighter." I

expected Christopher to say "oh, for God's sake" - but he had a curiously

unexpected reaction. He became immediately sympathetic and equally keen on the

quest to regain the lighter. I was actually deeply pessimistic but Christopher

was the one saying we should go back. So we trailed back and indeed, did find

it.

There are long gaps when we don't see each other. My

availability has always been the spanner in the works. To say in six months'

time I will commit myself to doing four performances is very difficult and I

have to learn an awful lot of text each time. It must be a bit - I feel -

irritating for Christopher.

If it hadn't been for the work I think we probably

wouldn't have become friends. Not at this stage in one's life. I know that when

we're going to come together again it'll be because of something we both enjoy

and want to do. Christopher is very dedicated and I admire his work

fantastically. I need him and I think he admires my work - so in a sense he

needs me, too.

Christopher Logue: We met because of Liane

Aukin. She rang me saying she would like to put War Music on the radio.

And she said the right person to do it would be Alan Howard. Now I'd seen Alan

in various things, chiefly in Peter Brook's A Midsummer Night's Dream.

But I hadn't seen him recently. So she said, "Why don't I drive you up to

Stratford, he's doing Richard II?" We went to see it and it was

absolutely wonderful. Alan caught that fantastic quality of obstinate weakness

that Richard has, at once charming and treacherous.

The following day I met Alan for the first time. He

was very diffident, not at all starry. He was rather nervous, walking around

the room, wondering whether he could take this thing on - the power and energy

he has on stage all concealed. I found that also with Robert De Niro, with whom

I did some work when he was in London. De Niro was living around the corner

from me, and said: "Why don't we walk across the park in the morning?" We did,

and nobody saw him at all. He was invisible. Alan can be the same. Even coming

out of the theatre, after a show, if Alan doesn't want to be noticed, he's not.

I find that very interesting indeed.

We next met at the recording, where I liked Alan very

much. I liked his humility about the text, and his anxiety to find out what

Liane and I thought about the way he was doing it. I was touched by this. At

the same time, within the diffidence was a confidence that he could do this

thing, and I find that a very attractive combination.

Mild disagreements have occurred all the time - if

they didn't there would be something wrong. I always want the untheatrical

thing, the news-reporter-weather-forecaster voice; Alan's tendency is to give

it the rhetorical Shakespearian voice. He gets rather nervous about putting

over another point of view. He starts to pace around, lighting cigarettes. Or

else he'll insist upon something completely irrelevant, like a certain kind of

coat he must have on.

Learning the text for the stage version of War

Music and Kings made the whole thing completely different. There's a

nervous side to it which to me is terrifying because I always think I'm going

to forget the lines. I once was the Player King to Jonathan Pryce's Hamlet at

the Royal Court. It was the worst three months of my life. When the show was a

success and we heard we were going to extend, my heart just sank.

Once you start to work with somebody on stage, you

become more protective of them. Automatically. In rehearsal Alan's diffidence

remains, but he has this tremendous power over his voice and can change it very

easily. When he's performing he's very certain of what he's doing. I see the

trouble I have in moving around the stage when Alan does it so easily. There's

a point where I had to move a stool and wasn't at all sure of the best way to

do it. I became dependent on him.

I have the text in front of me all the way through,

so I'm doing prompt as well as playing my part. Alan very rarely needs a

prompt. He does what he calls "knitting" instead: if it starts to go wrong he

just makes it up until he's back on track again.

Alan is definitely low-key. Then he gets on stage

and, zip, up comes the energy. He's also diabetic and I'm sure this is a very

important thing in his life. When we were on an Arts Council tour in Greece,

around 1989, I would get very concerned and say: "Now have you got your Mars

Bars?"

Alan is quite superstitious. He had this - it's gone

now, fortunately - cigarette lighter, on which he was extremely keen, it was a

sort of lucky charm. We went to a café in Athens and we were walking,

walking, walking to see some Byzantine church and Alan suddenly said, "I've

left my cigarette lighter behind", and the whole sort of thing collapsed for

him and we had to hurry back. Fortunately it was still there. Bit of luck. He

smokes far too much.

Our friendship has grown out of the work. It's only

recently after working with him for all these years that we've actually began

to talk about other things. No small talk at all. I'm not much good at it

myself, unless I'm with somebody who I know really well.

We don't meet, we talk on the phone when there's

something to talk about. I find it rather annoying that long gaps go by and I

haven't had contact with him at all. But I find that with quite a lot of my

relationships. Because I'm 70 and have so much work still to do, I'm incredibly

mean with my time.

Marianne Brace

Independent on Sunday, 30.3.1997.