Production Information

Article / The Independent On Sunday / 17.5.92

Review / Daily Mail / 10.4.92

Review / Observer / 12.4.92

Review / Daily Telegraph / 13.4.92

Review / The Independent / 11.4.92 / below

|

Production Information Article / The Independent On Sunday / 17.5.92 Review / Daily Mail / 10.4.92 Review / Observer / 12.4.92 Review / Daily Telegraph / 13.4.92 Review / The Independent / 11.4.92 / below |

Theatre / A perfect first night for the classless society?

|

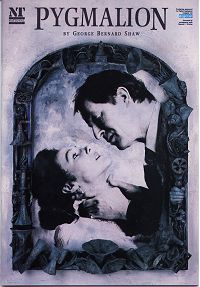

Viewed from a distance, the poster for the new National Theatre production of Pygmalion looks as though it might be advancing the sort of romantic falsification of Shaw's play that we find in My Fair Lady. Eliza stares up into the eyes of Professor Higgins who looms over her in what could be that tense moment before a passionate first kiss. Once you get nearer, however, you see that this is an optical illusion. The Professor's hands are wrapped ominously round his pupil's throat and the pose and the facial expressions are more suggestive of a vampire and his victim than a pair of incipient love-birds. Howard Davies's sumptuous revival is a total delight, and often hilariously funny, but its great strength is that it manages to be so at the same time as sharply insisting on the uncomfortable, anti-romantic elements in Shaw's reversal of myth: his Pygmalion takes a warm, feeling individual and tries (by improving her accent) to turn her into a social statue. All languid boorishness and spoilt little boy sulks, Alan Howard's excellent Higgins makes sure that you spot the irony that, not withstanding his superior vowel sounds, the Professor's manners are far worse than Eliza's. |

|

His experiment leaves her stranded, dissatisfied with her old life but unequipped for another, a fact which this production emphasizes in a dream-like sequence where her triumph at the ambassador's ball turns into a Cinderella nightmare of exclusion as she blunders unnoticed among the swirling couples.

A grimy, boyish urchin in her cockney incarnation, Frances Barber's delectable Eliza is quite hysterically comic at the nerve-wracking halfway stage when her character has acquired an effortful upper-class accent, while retaining a decidedly lower-class sense of grammar and conversational range.

At the famous tea party, she holds herself with the gingerly stiffness of someone wearing a neck brace, and heaps pedantic (if not always accurate) pronunciational care on the lowlife saga of her aunt's death. "Them she lived with would have killed her for a hat-pin, let alone a hat" she says, with lavish aspirates and sounding marginally less natural than a speak-your-weight machine. Her timing in this scene is brilliant: you keep thinking she's finished and that you can stop sweating for her; then she plunges on.

Barber is just as impressive in the later stages of Eliza's development, letting you see all her pain and disorientation and conveying, with touching dignity, the new astuteness and maturity that enable her to perceive that the real difference between a lady and a flower-girl "is not how she behaves, but how she's treated."

Subtle about the play's odd emotional currents and full of splendid performances (Michael Bryant's engagingly venal Doolittle; Robin Bailey's drolly dessicated Pickering) the production is a continuous pleasure simply as a spectacle. Making maximum use of the revolve on the Olivier stage, William Dudley's enchanting designs take the play out into the misty London streets with their cabs and lamp-posts.

When Eliza returns home after her first encounter with Higgins, a combination of smoothly revolving scenery, a melting succession of back projections and a mobile gantry bridge create a magical illusion that we are following her through the city.

At the end when he predicts that she will marry Freddy (Simon Coates), there's just enough hysteria in Higgin's derisive, incredulous laugh to make you think that there might be a tincture of jealousy in his response. But Howard rightly plays him as a man who is made uneasy by the idea of sex and who wants Eliza to stay on as a third bachelor in a sexless menage a trois with him and Pickering. This production rules out the possibility of any future romance. It also decisively scotches the myth that My Fair Lady is a greater work of art than Shaw's play.

Paul Taylor.

The Independent, 11.4.92.