|

The Tempest Roundhouse experiment

notwithstanding, far from neglecting the text of a play, Brook's involvement in

a work which interests him is total. For this Shakespeare comedy, his actors

must never be allowed to forget that they are playing in the context of

continual stage happenings, a world 'swift as a shadow, short as any

dream'.

'After a long series of dark, violent, black

plays I had a very strong wish to go as deeply as possible into a work of pure

celebration. A Midsummer Night's Dream is, amongst other things, a celebration

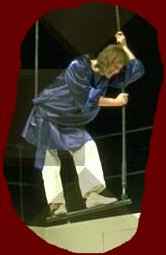

of the arts of the theatre. On one level the actors have to display a physical

virtuosity - an expression of joy. Hence our production at Stratford involves

acrobatics, circus skills, trapeze acts. Equally, certain parts of the play

cannot be played without using a Stanislavskian sense of natural character

development. There's the play we all know - and also a hidden play, a hidden

Dream. That's the one the actors set out to discover for

themselves.

'The Dream is a play about magic, spirits,

fairies. Today we don't believe in any one of those things and yet, perhaps, we

do. The fairy imagery which the Victorian and even post-Victorian tradition has

given us in relation to the Dream has to be rejected - it has died on

us. But one can't take an anti-magical, a down-to-earth view of the

Dream. When I directed Titus Andronicus at this theatre sixteen years

ago I was convinced that the play wasn't just a series of gory events but was a

hidden play - the drama behind Titus was a ritualistic expression

of a primitive cycle of bloodshed which, if touched, would reveal a source of

immense, atomic power. In the same way, the interest in working on the

Dream is to take a play which is apparently composed of very artificial,

unreal elements and to discover that it is a true, a real play. But the

language of the Dream must be expressed through a very different stage

imagery from the one that served its purpose in the past.

'We have dropped all pretence of making magic

by bluff, through stage tricks. The first step must be moving from darkness to

daylight. We have to start in the open - in fact we begin in a white set and

white light (the only darkness in the entire production occurs during the

public encounters between Theseus and Hippolyta). We present all the elements

with which we are going to work in the open. This is related to one of the key

lines in the play when the question arises about whether the man who is going

to play the lion should be a real lion or only pretend to be real. Out of this

academic and very Brechtian discussion comes the formulation that the actor

should say to the audience, 'I am a man as other men are'. That is the

necessary beginning for a play about the spirit world - the actors must present

themselves as men who are like all other men. It's from the hidden inner life

of the performer that the magic, the unfolding possibilities of the play, must

emerge. The core of the Dream is the Pyramus and Thisbe play which

doesn't come at the end of a highly organised work just for comic relief. The

actor's art is truly celebrated in this episode - it becomes a mysterious

interplay of invisible elements, the joy, the magic of the Dream. The

play can become an exploration, through a complex series of themes, of what

only the theatre can do as an art form.'

Brook has several of his actors doubling, even

trebling their roles in the play. Most notably Alan Howard and Sara Kestelman

play both Theseus-Hippolyta and the fairy king and queen, Oberon-Titania. Was

this for thematic or economic reasons?

'There were two motives. Firstly I wanted to do

the play with a small group. There is a quite different quality of involvement

with such a group than with a large cast where the actors come on, do a little

bit and then disappear for the rest of the evening. When I directed the RSC

experimental group in a version of Genet's The Screens we used a small

group in which one actor played two, even three, roles. In this way you can

take an actor much further - if he reappears in a different part during a

performance. Close to this was the fact that in the Dream there are no

set characters - the more you study the comedy it becomes a comment on what

makes a dream; each scene is like a dream of a dream, the interrelation between

theme and character is more mysterious than at first sight. Theseus and

Hippolyta are trying to discover what constitutes the true union of a couple,

what can bring about the conjunction whereby their marriage can become true and

complete. Then a play unfolds like a dream before their wedding in which an

almost identical couple appear - Oberon and Titania. Yet this other couple are

in an opposition so great that, as Titania announces in language of great

strength, it brings about a complete schism in the natural order. She claims

that her dispute with Oberon is the cause of the whole world going awry. Thus

on the one hand we have a man and woman in total dispute and, on the other, a

man and woman coming together through a concord found out of a discord. The

couples are so closely related that we felt that Oberon and Titania could

easily be sitting inside the minds of Theseus and Hippolyta. Whether from this

you say that they are actually the same characters becomes

unimportant.'

I then asked Brook if he shared Jan Kott's view

of the Dream - that far from being a 'celebration' the play contained a

darker, more sinister exploration of love than is normally suggested. 'Most

definitely. Kott wrote very interestingly about the play - though he fell into

the trap of turning one aspect of the play into the whole. The Dream is

not a piece for the kids - it's a very powerful sexual play.

'There is something more amazing than in the

whole of Strindberg at the centre of the Dream. It's the idea, which has

been so easily passed over for centuries, of a man taking the wife whom he

loves totally and having her fucked by the crudest sex machine he can find. We

had a long discussion about this at one point in rehearsals - we listed all the

alternative animal-mates with which Titania might have been presented by

Oberon. One realises that every other animal could have left Titania with a

certain sexual nostlagia - it's a sort of romantic dream for a woman to be

screwed by a lion or even a bear. The ass, famous in legends for the size of

its prick, is the only animal that couldn't carry the least sense of romantic

attachment. Oberon's deliberate cool intention is to degrade Titania as a

woman. Titania tries to invest her love under all the forms of spiritual

romance at her disposal - Oberon destroys her illusions totally. From

Strindberg to D.H. Lawrence one doesn't find a stronger situation than that.

It's not only an opposition between this ethereal woman and a gross sensuality

that's coupled between Titania and Bottom - but the much darker and curious

fact that it's the woman's husband who brings this about - and in the name of

love! Yet there's no cynicism in Oberon's action - he isn't a sadist. The play

is about something very mysterious, and only to be understood by the complexity

of human love.'

If it is part of Peter Brook's intention to

lead his actors through 'most of the schools of theatre that we know' during

their performance of the Dream, it is also part of a preparation for a larger

experimental programme which Brook is finally to begin in Paris this October.

He has been trying to find a subsidy for his room in the French Ministry of

Works, his 'empty space', for the past two years. As there are to be no public

performances money has been difficult to find - but, of all places, a subsidy

has finally come from Persia.

I asked Brook why so many directors were

currently questioning the value of the work they were doing, uncertain about

the state and future of our theatres themselves. Typically, he answered with

confidence and faith. Unique among our directors, Brook has been questioning

the meaning of conventional theatre for years. Equally strangely he has been

searching for and inventing new forms on his own, as though bent on rescuing

the art of the theatre for a future, unknown generation:

'All questions of this sort exist or disappear

in relation to the level of intensity that is reached. A low level Shakespeare

production sets up boringly archaic barriers for an audience - all that is true

life is only dimly perceived. All that is lukewarm, passive, conventional in an

audience is brought into play. At that level one has to question the meaning of

a performance - to ask what social function it performs.

'Above that, there's another level where in

place of a lack of an intention, an intention appears. With that intention,

which may be political or social, comes a force, a clarity of purpose and a

meaning. It might involve doing a play about a dock strike in the right place

at the right time.

'Then you approach the next level, which

includes very few writers (of which Shakespeare is the strongest and most

unique example), when you suddenly discover an essential area where meanings

between actors and an audience can be shared again, on a very different level

to, say, a treatment, of a dock strike - but a meaning which is quite tangible.

This form of intensity makes all questions of the play's relation to the past

unimportant. It's happening now - whether the characters appear to be archaic

or contemporary in their costumes and behaviour. All theatre begins when it is

alive - all other theatre is dead. The theatre event that increases our power

to perceive is something rare but, to my mind, to be cultivated at all costs.'

Peter Brook talks to Peter Ansorge.

Plays and Players, October

1970. |