|

This programme is actually as black as it appears! HAMLET is embossed on the front. |

|

I hope Trevor Nunn and his talented company were not depressed by the first night notices accorded their Hamlet. If they care to study the daily reviews of Peter Hall's revival on the same stage five years ago and indeed if they care to take a really careful look at the overnight clippings of the century's now legendary revivals they will discover precious few bouquets amongst the fading print. I'm not saying that thumbs down in Fleet Street is to be equated with perfection at Stratford the night before. But I do think that a detailed, ensemble production minus flashy star turns and minus spectacular applause-invoking settings is unlikely to lead to Instant Acclaim. That notwithstanding, I suggest this Hamletdeserves to follow Nunn's revivals of The Revenger's Tragedy and The Winter's Tale into London where I believe the Aldwych's young public will recognise and appreciate the stylistic affinities running through a trio of productions in which the RSC may take especial pride. |

|

It is the continuity in approach that makes it hard, for me at any rate, to see this Hamlet revival in isolation - or indeed to recommend it to your attention simply because of Alan Howard's performances in the title role, for the excellence of Brenda Bruce and David Waller as Gertrude and Claudius, for the quiet authority of Sebastian Shaw's restrained Polonius, for the lucid simplicity of Christopher Morley's black and white setting, for the satisfying support of Guy Woolfenden's music and John Bradley's lighting. Regular visitors to Stratford and the Aldwych will recognise in these names many of the credits for both The Revenger's Tragedy and The Winter's Tale and will perhaps sympathise with me in being unable to assess this Hamlet merely as a histrionic Aintree for Alan Howard even if , in fact, he made the course where so many (sometimes eminent) thoroughbreds once came painful croppers.

|

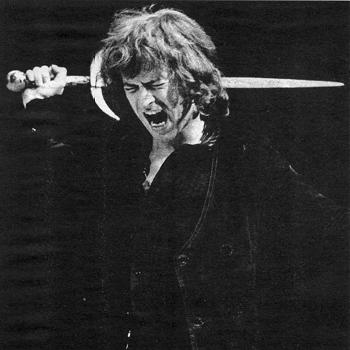

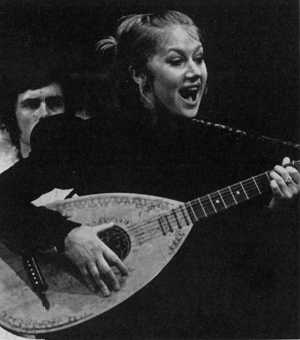

Of course the gallery girls who used to swoon when the Prince of Denmark was embodied by Richard Burton and John Neville are likely to see this latest lean not to say weedy Hamlet through eyes less enthusiastic than Helen Mirren's Ophelia. It's Christopher Gable's personable Laertes who is likely to bring in the fan letters. But then the girls ought to be glad that the Howard Hamlet's hysterical outburst after his initial encounter with his dead father did not, after all, preface a trendy portrait of another royal boy in the band. If this Hamlet loves his Horatio it's not because he's queer but because he has the insight and self-knowledge to recognise that unlike his chum he is all too easily passion's slave. And he even goes to the length of giving himself a slow hand-clap when he catches himself carried away by a torrent of words and feeling. So? So those who repair to Stratford in search of a Prince Charming will, I'm glad to say, be disappointed. But those who recognise in Hamlet an intelligent and not insensitive neurotic making a desperate and ultimately successful bid to come to terms with himself will find something of what they are looking for. |

|

The enclosed space carefully defined in Christopher Morley's setting gives this production a distinctively domestic aura in which a few highly selective props (as in The Winter's Tale) are used to help elucidate the text or give it an ironic resonance. The steeply raked stage of white floorboards, the white tables and desks, the plunging ceiling, the Venetian blinds all make one think of an elegant palace rather than a fortress castle. I was often in fact reminded of the real Elsinore we glimpsed in an unfortunate television production filmed on the Danish location. At all events the outside world in this production is implied rather than stated. We are free to see one family (the Polonius', who are here rather a pleasant lot) engulfed by the tragic resolution of the relationships in a royal family who, in this production, are particularly unpleasant.

|

David Waller's Claudius is the most bloated and boorish I have seen. We first glimpse him 'as from the coronation' giving his opening speech as a royal proclamation to the court (played here by us, the public). The royals are lined up front stage and the Polonius' (all unknowing of their fate) listen to the wordy peroration with a public showing of polite fortitude. The formalities over, the line-up is broken and the court retreat to the intimacies of their own Palace Revolution. Brenda Bruce's Gertrude is a blonde sexpot barely concealing her boredom with Higher Things with the perfunctory sign of the cross when passing through the court chapel. Her favourite moue consists in raised eyebrows and lips apart with a tongue held provocatively out. As the play begins she and Claudius (on whose bulky frame she likes to silkily cuddle) are evidently in a sensual paradise. It is only when her son points to the portraits on her dressing table of a first and a second husband (the former reappearing in a nightshirt and patently a figment of Hamlet's imagination) that their relationship is shattered. Although Claudius beats up a stripped Hamlet to discover where he has hidden the body of Polonius he is a broken man thereafter. Indeed he is so overcome by the loss of the love and then the life of his queen, he capitulates entirely to Hamlet in the distraction of his defeat. The potion is meekly drunk. |

|

At a first viewing, there seem to be three distinctive and interrelated aspects to Trevor Nunn's minimally cut revival of Hamlet that contribute equally to its success. The first, as I have already remarked, is a precise and selective placing of the drama in a domestic context. The second is an interesting deployment of a Pirandello-like concern with the nature of illusion and reality. The Players, the only characters not to be dressed either in black or white and carrying with them a visual hint of hippiedom, perform in a stylised manner reminiscent of Oriental theatre. But, for the first time in my experience, they also come across as so many characters in search of an author - a staged and stylised reflection of a tragedy being enacted by their Royal public. Claudius himself is mesmerised into intruding on stage when he can no longer stomach the playing out of his crime. And his prayer for the pardoning of it is made kneeling over the spot where an actor recently impersonated the victim over which he grieves. Hamlet, the meanwhile, dithers about polishing off his uncle from behind the back curtains of the Players' improvised stage. Later it is one of the actor's discarded costumes - a monk's habit - that he snatches up to wear in his late-night bedroom meeting with his mother. And, always given to playacting, it is as much as a priest as a son that he chides Gertrude.

Thirdly, and most importantly, is Nunn's persistent highlighting of Christian symbolism in the text. Hamlet, who is discovered wearing a crucifix at the opening of the play, takes on the appearance of Christ being deposed from the cross when Claudius beats him up in front of a large Court cross after the murder of Polonius.

|

Earlier, 'To be or not to be', is conducted in the form of a meditative prayer whilst kneeling at the altar of the Court chapel where Ophelia is seated at a pew and Claudius and Polonius have retreated into two confessionals to eavesdrop on Hamlet and Ophelia. Incidentally at this point a modern audience is bound to put a modern interpretation on this encounter between the Prince and his lady-love. At least they ought to for, as Hamlet himself says, 'the purpose of playing is to show the very age and body of the time his form and pressure'. In these times the natural question will be especially to speculate whether Ophelia and Hamlet went to bed and, if so, whether the Prince did so out of lust or love. His 'I loved thee not' and her 'I was the more deceived' come across as a brutal wish to indicate the former and give the scene an added poignancy. It also accounts for the extreme lewdness of the song recital Ophelia treats the court to before her suicide. |

|

|

Fleet Street not withstanding, then my pay-off line had better be 'How about a transfer?' Peter Roberts Plays and Players, July 1970. |

|

| Back to RSC Reviews page |