|

|

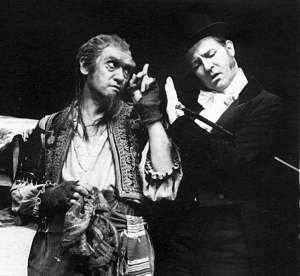

Thwarted young love caught in the grip of a scheming matriarch's avarice is not a particularly new story, and Alexander Ostrovski's The Forest dates from 1871. But in delving into Russia's rich hoard of drama once again, the Royal Shakespeare Company at Stratford's The Other Place, has come up with a play which uses an old theme to reveal the petty corruption and false values of the landed gentry. Barbara Leigh-Hunt, clutching her money chest wherever she goes, sets about her scurrying household and wide-eyed, lovelorn ward (Janine Duvitski) with rapacious efficiency. Such domestic tyranny has been quite enough for many a good play. But Ostrovsky introduces two complementary personalities of outsize breadth and eccentricity. Their arrival through the wooded estate to claim the kinship of of one of them to its haggling owner shows up the conflict between aspirations and false values which turns up again and again in this writer's work. It is tempting to find comparisons for this extraordinary pair of provincial actors. Alan Howard is the tragedian in grand vein, with grey sombrero and shabby greatcoat. His wildness of eye conjures up again his performance as Jack Rover in O'Keefe's Wild Oats for this company, but with an added subtlety of tone and gesture that sets this other petty world spinning. It is a marvellous performance. |

|

His companion, played by Richard Pasco, is a Sancho Panza figure, already relegated from comedy roles to prompt corner, who finds a place beside his master, ready to regale him with theatre memories, quips and sallies.

Adrian Noble's production allows a freedom of expression on an uncluttered wooden floor that makes for company playing of the highest order, and, with Miss Duvitski's despairing attempts to drown herself in the lake, a strangely moving example of unexpected heroism from Alan Howard's flamboyant tragedy king.

This is perhaps the most successful of Jeremy Brooke's and Kitty Hunter's translations from the Russian for the RSC. I hope they will be asked to do more of this playwright.

Rosemary Say.

The Sunday Telegraph, 3.5.81.

|

Splendid! A new Russian classic enters the English repertoire with all the elements that a Russian classic should possess. The Forest, by Alexander Ostrovsky (The Other Place), has a landowning widow who lives by selling off tracts of timber, forever at the mercy of the rising merchant class. And if you think that is a bit fishy, I might add that in another of Ostrovsky's plays, there is a heroine whose name means "the seagull", whose life has been destroyed "by a passing lady-killer." Ostrovsky (who died in the year that Chekhov embarked on serious drama with Ivanov) survives in the international repertoire on the basis of Thunder, which Janacek turned into Katya Kabanova, and as author of The Snow Maiden, which both Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov set to music. Thunder was translated into English in a useful but rare Penguin Classic, "Four Russian Plays" (1972), by Joshua Cooper. In other words, Ostrovsky, like Victor Hugo, is familiar as a playwright, but not among the English theatre-going world. |

|

That stage of affairs will now change. Jeremy Brooks and Kitty Hunter Blair have produced a new translation of The Forest, which in Adrian Noble's production is both as exciting as this director's recent Duchess of Malfi, and also considerably less bloody. The comedy is boldly conceived, and the production takes a delight in mixing a natural style with the most vivid caricature. Caricature is often used as a perjorative term in criticism. But true caricature is a most difficult and rewarding art, requiring absolute accuracy and continual strength of line. I knew that I was going to love this production when Eve Pearce flitted across stage as the eavesdropping housekeeper, drawn inexorably to the scene of any possible scandal, and possessed of an ability to become invisible to the characters on stage while remaining, in fact, in full view. Wide eyes darting to and fro, a face across which it seemed impossible that a smile should flicker, she looked like a Russian version of Mrs Danvers in Rebecca.

The housekeeper is right-hand woman to Barbara Leigh-Hunt, the land-owning widow, a character of fundamentally malicious disposition. There were occasional moments of slight panic when I thought that either Osrovsky or Miss Leigh-Hunt was going to attempt to redeem this figure in our eyes, and display some element of fine feeling. But no, thank heavens. She kicks off hypocritical, continues as scheming, selfish, and cold, and brings the portrayal to a wonderful climax of meanness, at a moment when a less whole-heartedly nasty character might have seen the opportunity for a grand public gesture.

She reminds us of an evil step-mother from a fairy story, and that, precisely, is what she is. Janine Duvitski plays the impoverished niece, betrothed against her will to a good-for-nothing for whom Miss Leigh-Hunt nurses a secret passion, Paul Whitworth. Miss Duvitski is a goodie - natural, loving, passiionate, but with a morbid tendency to think on suicide. Mr Whitworth is shallow, affected, cowardly, with his eye on the main chance, and with a comical faith in his ability to come across as a swell. How could true love light upon such a character? No, Miss Duvitski's affections are elsewhere, and a glance at the cast list is enough to tell you where. True love is Allan Hendrick. True love is always Mr Hendrick. He's the one who can do sincerity. But how to get the dowry necessary for the betrothal to Mr Hendrick?

|

It is here that the two comic master strokes of the piece are played. Along through the forest, hopelessly down on their luck, come a tragic actor (Alan Howard) and an old vaudeville player (Richard Pasco), who having met by chance, decide to try out their fortunes chez Mr Howard's mean aunt (Miss Leigh-Hunt). Mr Howard is as mad as a meat axe: when he thinks of the way the acting profession has degenerated and been handed over to university men and puny tenor voices, when he thinks of the fine qualities of his own bass voice, when he contemplates his fallen splendour - well, you feel that anything could happen. And that, too, is what the nervous Mr Pasco feels, as he inquires in awestruck tones: "Were you ..........very good?" It is a line which produces one of the best laughs of the evening, as these two of the season's heavyweights display all their skills for our amusement. Mr Pasco matches Mr Howard's tendency to grand gestures with a wonderful display of broken-spirited servility. At the great house, where Mr Howard passes himself off as an officer in order to impress his aunt, Mr Pasco is cast in the role of Sganarelle, a role he understands perfectly. He must serve, but he must finally rebel. For that fatal tendency of Mr Howard's to indulge in the grand gesture will ruin both their futures. We see in the denouement how his romantic nobility of spirit has brought this actor down. |

|

The work is rewarding for all the players - for Dennis Clinton as the servant, Hugh Ross and Raymond Westwell as the rich neighbours and for Paul Webster as the timber merchant. I do not think there is a weak spot in the whole company. As for Mr Noble, who must just be recovering from the extravagant praise heaped on his Webster production - it would be very suspicious, would it not, if Mr Noble were to be walking into the main house one day, when a gigantic flowerpot was dropped on his head, and one of our other bright young directors was seen scuttling away over the rooftops?

Very suspicious indeed.

James Fenton.

The Sunday Times, 3.5.81.