|

Most difficult of all, of course, is the task

of hacking a clear path through the adulation and scorn that seem invariably to

be engendered by a new Brook production. Whether he is directing Olivier and

Vivien Leigh (in Titus Andronicus), the Lunts (in The Visit) or

John Gielgud and Irene Worth (in the Seneca Oedipus) somehow the

originality of his approach has counted for more than the drawing-power of

these luminaries - even if their careers have only been rendered more

distinguished in the process. All of which has somehow resulted in Brook being

dubbed a quintessentially intellectual director - the suavest insult an

Anglo-Saxon can bestow on another. This, in turn, has sometimes resulted -

probably as a consequence of the tortuous prose he can sometimes perpetrate -

in his also being labelled simultaneously academic and pretentious. I cannot

speak at first hand of what Brook did with decidedly unintellectual and

unacademic material like The Little Hut, but on the evidence of his

book, The Empty Space, as well as on what can glean of his current

working methods he is the most pragmatic of theatre men whose rehearsals are

genuine acts of exploration rather than putting into effect cut and dried

preconceptions of the study.

A starting point for rehearsing this production

of The Dream would seem to lie in a quote from The Empty Space.

It reads: 'It has been pointed out that the nature of the permanent structure

of the Elizabethan playhouse, with its flat open arena and its large balcony

and its second smaller gallery, was a diagram of the universe as seen by the

sixteenth-century audience and playwright - the gods, the court and the people

- three levels, separate and yet often intermingling - a stage that was a

perfect philosopher's machine.'

In this production those who intermingle are

the audience and the actors even if this is no arena stage revival. The

audience participates to the extent that they are made to feel they are

watching from the wings rather than the auditorium and their involvement - at

least on the opening night, was such that they eagerly clutched the cast's

hands as they burst up the aisles in response to Puck's closing

request

Give me your hands if we be friends,

And Robin shall restore amends.

Above all it must be stressed that the

production had been fun - a joyous celebration of the actors' skills in which

the limitation of these in the classical field to intelligent vocal

manipulation of the verse had been smashed through as only a part of a more

acrobatic concept of the actor as a conjuror, a trapeze artist - a being with

one foot in the circus and one on Shakespeare's text. It was immensely cheering

to see the final vestiges of the idea of a Shakespeare actor being essentially

a rather dignified declamatory artist so boldly jettisoned whilst the verse

itself remained unmutilated.

All this takes place at Stratford in a bare and

consistently brightly lit set which has the three levels of the Elizabethan

Playhouse without being in any sense a reproduction of them. There is the

audience level on which the cast make their contact with the public at the

close of the play and on one or two other occasions earlier on in the

proceedings. And there is the stage level which proves to be an enclosed white

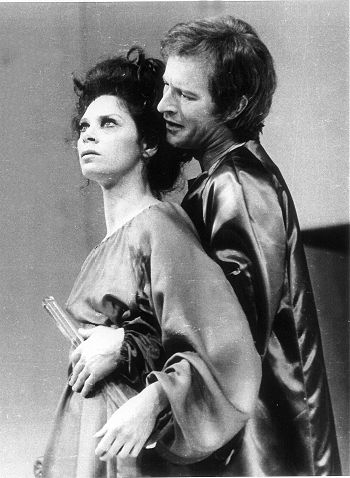

space - a room with two doors at the rear through which Alan Howard, as

Theseus, and Sara Kestelman, as Hippolyta, enter - separately and with dignity.

Subsequently, having dealt with equal dignity with the cross Egeus and the

Lysander/Demetrius Hermia/Helena entanglement he precipitates, they exit as

Oberon and Titania to enact what I take to be a pre-marital dream on the part

of Theseus.

For the working out of this dream a third level

- equivalent to the balcony of the Elizabethan stage - has to be arrived at. In

fact the parallel is provided by a cat walk round the top of the room that

constitutes the principal acting area of Sally Jacobs' set. On this narrow

balcony are variously distributed the musicians (in modern dress and performing

displaced sound effects in full view of the public) and, at times, the fairies

who take on the form of modern dress puppeteers dangling massive steel fishing

rods that have the purpose both of suggesting that the quartet of lovers are

manipulated marionettes and, at the same time, have the practical function of

suggesting the trees that are supposed to grow in the wood near

Athens.

So the magic in The Dream, usually dealt with

on stage in the nursery terms of tittuping fairies and fat jolly avuncular

actors wearing loveable asses' heads is flushed this year smartly into the Avon

like so much effluent. In its place, we have the rougher magic of the circus,

of the puppet theatre and of the music hall. Thus Bottom sports a clown's nose

when under the influence of the potion, love in idleness; thus we have Titania

floating down from the flies in a crimson bower of ostrich feathers straight

out of a folies bergères review; thus we have Puck in yellow pantaloons

trailing with him memories of the sturdy accomplishments of the commedia

dell'arte troupers; thus we have Oberon nonchalantly spinning a saucer on

the end of a stick whilst airborne on a trapeze. To say all this proved

exhilarating would be the understatement of the year. |